Home Ec: A Guide to the Knives You (Actually) Need

Let's talk knives for a moment.

I'm thinking about the knife skills class I'll be teaching as part of the Home Ec series at 18 Reasons next month, putting together a list for my students.

Over the years as I've guided plenty of professional and amateur cooks toward cutlery purchases, it's come to my attention levels of insanity at the knife shop can seem, at times, to be directly correlated to testosterone levels and the amount of food television watched.

Ahem.

All I'm saying is that some of the best chefs and cooks I know have some of the humblest knives. A fancy, long, expensive Japanese knife does not necessarily a good cook make.

Tamar's book has done a lot to remind me of the value of amateurism. So many of the problems that home cooks face result from a cultural tendency to conflate what is appropriate and/or necessary in a professional kitchen with what is appropriate and/or necessary in a home kitchen. That conflation, or confusion, really, is actually just a terrible story being told to us by the people who want to sell us more crap and make us think that we can't cook, and cook well, without every single doohickey they're trying to get us to buy.

However, having the proper tools on hand definitely makes things smoother, easier, and more comfortable. And frankly, you waste a lot less when you use the right, sharp knife for a task.

For most home cooks, three, maybe four knives are plenty. When I'm too lazy to unpack my knife roll at home, I often get away with just a chef's knife and a bread knife.

Knife blocks are a waste of space, and sort of silly, if you ask me. Knife sets are just ways to get you to spend way more money than necessary. Expensive German and Japanese knives are nice, and can definitely feel really luxurious, but I tend to think of them more as fancy cars than workhorses.

I've done my best to put together a no-nonsense knife shopping resource for you. I hope it explains what needs to be explained and guides you toward purchases that make sense for you, and most importantly, help you feel at home in the kitchen.

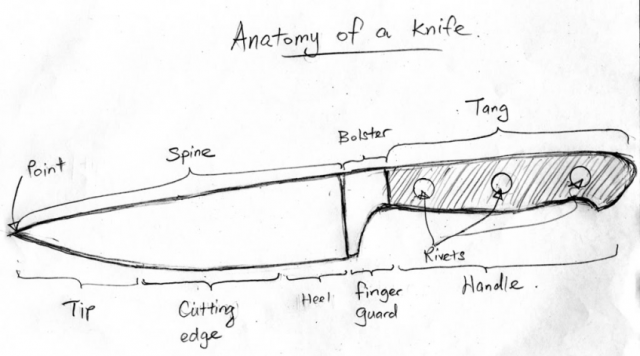

illustration from MarshallMatlock.com

Glossary

Forged Blade: A blade shaped by pounding a single, thick piece of heated steel under extreme pressure using a hammer and die.

Tang: The part of the knife that extends into the handle. On a typical wooden handled knife, you can check the length of its tang by looking at the top of the knife handle and seeing how far the metal extends.

Stamped Blade: A knife blade that's stamped from a piece of steel, much like how a cookie cutter stamps cookies out from dough.

Bolster: The knob of steel located at the back of the blade, where it meets the handle. Typically, forged knives have bolsters while stamped knives do not.

Carbon Steel: The metal of choice back in the day. It can get really, really sharp, but dulls quickly and rusts, so most knife makers have abandoned it in favor of stainless steel.

Stainless Steel: The metal of choice these days, because it doesn't corrode or rust, but the average stainless steel blade can't get as sharp as its carbon steel counterpart. However, the higher quality the steel, the fancier and more expensive the knife. Some Japanese knives are made with extremely fancy stainless steel that can actually get sharper than carbon steel, and hold an edge for even longer, too.

Sharpening: Redefining the edge of a knife's blade by using a sharpener or whetstone. Sharpening a knife blade actually whittles away a fine layer of its metal, giving it a completely new edge that's ideally set at an angle that will allow you to cut thinly, quickly, and easily. A well-set edge will last several weeks to several months, depending on how much you use your knife, how well you take care of it, and what material it's made of.

Honing: Running a knife blade across a honing steel to realign all of the little metal teeth that get all mixed up each time you use a knife. Honing does not actually sharpen a knife, extending the lifespan of a sharpened blade instead.

Forged versus Stamped Blades

Let me break things down for you. Basically, there are two methods for constructing knife blades: stamping and forging. Generally, stamped blades are considered to be of lesser quality and forged blades of higher quality.

A stamped blade is cut, or stamped, out of a roll of steel, and then handles are attached. Since there is no bolster, and since stamped blades tend to be on the thinner side, a stamped knife is typically lighter and less expensive than its forged counterpart.

Though stamped knives are often considered, and often are, inferior to their forged brethren, there are some great knives with stamped blades out there, appropriate for both professional and home cooks. Global knives, omnipresent in restaurant kitchens and on cooking shows, are among the highest quality (and most expensive) stamped knives out there, though I don't much care for them myself.

I'm a huge fan of Victorinox-Swiss Army (formerly Forschner Victorinox) knives with rosewood handles. I can't tell you how many of these knives I have owned, given away, and recommended over the years. Made in Switzerland by the same folks who've been making Swiss Army knives since the 1880s, this line of stamped knives is well-constructed, durable, and completely reasonably priced. The wooden handles are attached with rivets, and the tang, while not full, reaches deep into the handle so there is little risk of the blade snapping off.

Forging a blade is a more complicated process which requires a more skilled hand, resulting in a better crafted, more expensive knife. In the process of forging a thick, hot piece of steel is shaped by pounding it with a forging hammer and die (think Hephaestus). Forged knives are also given bolsters, or thick pieces of metal where the blade meets the handle that can serve to protect straying fingers and offer balance between the blade and handle. Because of the bolster, and the thicker steel, forged knives are often substantially heavier than stamped knives, which can be useful for chopping, but which can also lead to fatigue more quickly. Forged knives often, but not always, have a full tang, which means that the knife is made from a single piece of steel from the tip of the blade all the way to the end of the handle. Besides being sturdier than a partial tang, a full tang will make a knife better balanced, which in turn can make it easier to use.

A lot of people, myself included at times, are really into Japanese forged knives, which can offer the best of both worlds--an extremely well-crafted yet light, thin bladed knife with superior design. Some of my favorite Japanese knives combine carbon steel, which can get really sharp, with stainless steel, which does not rust, for blades that sort of do it all. The thing is, Japanese knives can get really expensive really quickly. Does the average home cook need a fancy Japanese knife? No. Will it make you a better cook? No. Will having one make certain tasks much more enjoyable? Definitely.

The most important thing to consider when buying a knife (assuming you've already checked to make sure that it's not serrated or micro-serrated, like a Ginsu) is how it feels in your hand--that's why I highly recommend going to a cutlery shop in person to try out knives before purchasing them. We all have different body types, hand shapes, and likes and dislikes, so different knives of equal quality will be preferable to each of us. That being said, the Victorinox Rosewood line is a great place for almost everyone to start--those knives are well-priced and well-made, not too heavy, not too light.

The Three (or Four) Knives Every Home Cook Needs

An 8-inch or10-inch chef's knife. If you prefer, you can choose a Japanese santoku knife instead, but since santoku blades are rarely longer than seven inches, this could prove frustrating when chopping large amounts of herbs, vegetables or greens. Since this Hiromoto 2800 santoku is relatively inexpensive (and really awesome), it might be the ideal gift to request for your birthday in a year!

A paring knife. I prefer bird's beak paring knives because they offer greater mobility and are really useful for trimming vegetables and other tasks that require a delicate, precise touch.

A serrated knife for slicing bread and tomatoes.

A boning knife with a thin, flexible blade is extremely useful for butchering and slicing raw and cooked meat. Anyone who plans to cook fish, chicken, or other meat at home should invest in one of these. I also LOVE this one with the granton, or dimpled, edge.

Basic Accessories

photo from Martha Stewart Everyday Food

Honing Steel. Rather than sharpening a knife, a few swipes across a steel simply realign, or hone, the tiny metal teeth along the edge of the blade. These teeth get out of whack each time you use the knife, and regular honing will extend the lifespan of a sharp blade, prolonging the time between each sharpening. Using a steel is not a replacement for sharpening your knife!

I love this black ceramic steel because I can use it with my Japanese knives as well as my Euro-style knives. It's also really sturdy, unlike most ceramic steels that will snap in two if you just look at them the wrong way.

Vegetable Peeler. These inexpensive Swiss vegetable peelers are the best, and their ergonomic design allows you to swiftly peel a pile of carrots without straining your wrist. I basically can't use any other peeler.

photo from Martha Stewart Everyday Food

Sharpener or Whetstone. Learning how to use a whetstone to sharpen knives is an invaluable skill that takes a bit of trial and error and a good dose of patience to master. But, in the long run, it's totally worth it because having sharp knives will become the rule instead of the exception in your kitchen, and sharp knives are not only more pleasurable, but also safer, to use.

If a whetstone just isn't your cup of tea, then consider getting a sharpener or commit to taking your knives to a local sharpener at least twice a year.

Getting Fancy

Fujitake, Misono and Hiromoto are three of my favorite Japanese knife makers. All of them make well-constructed, gorgeous knives that are a pleasure to use. I have a Fujitake 240mm and Hiromoto 180mm that use all of the time.

Mac Knives are sorta hip these days. I've been through three of these over the years (between losing them and just sharpening them down to nothing)....they are invaluable for fine slicing and dicing if you find yourself doing that kind of thing.

Cut Brooklyn. Simply beautiful. A total luxury.

Cleaver. I have and love an older version of this cleaver from Due Cigni. If you plan to buy whole chickens, ducks, or work with any other meat bones, a cleaver is handy. I was taught never to use a knife to cut through bone, and grimace every time I see someone do it.

Saladini knives. Scarperia is a medieval hamlet in the Tuscan foothills with a rich history of ironworking and knife-making. In the fifteeth and sixteenth centuries, knives from Scarperia were unparalleled in quality, and by the late 1800s, the town had become recognized throughout the country as the home of Italy's most skilled knife-making artisans. As a result of industrialization and the passage of laws prohibiting the production of certain types of knives in Italy, only a few knife makers remain in Scarperia today, down from something like 80. Saladini is by far my favorite. I spent some time in their workshop when I lived in Tuscany when I chose each and every handle for the steak knives we used at Eccolo. The level of craftsmanship is extraordinary, and all of the horns the handles are carved from are naturally shed.

Vintage Sabatier Carbon Steel Knives. I'm obsessed with these beauties.

Knife Shopping Resources

In the East Bay

In San Francisco

Online

- My Guide to Basic Knives for the Home Cook on Amazon

- Cut Brooklyn: Gorgeous artisan knives. Made by hand in Brookyln, NY.

- Orchard Steel

- Chelsea Miller Knives

- Korin Japanese Knife Shop

And finally, here is a gorgeous video profile of Joel Bukiewicz of Cut Brooklyn, with shots of him working on the knives, at various points in the forging process.